FEBRUARY 5, 2018 (PITTSBURGH, PA) – Microbac Laboratories, Inc. today announces a new strategic partnership to offer clients the R&D consulting services of MedSurgPI - a team of commercially experienced pharmaceutical and medical device consultants. Click to read full story.

Technology Commercialization Group, LLC (TCG) Announces a Strategic Partnership with MedSurgPI, LLC →

Common Shortfalls in Clinical Supply Chain Planning →

We have been amazed at the complexity of the journey of clinical supplies to investigator sites is and delays can be extremely costly for sponsors. In fact, supply chain logistics can account for up to 25% of total annual pharmaceutical R&D costs. With stakes this high, it’s important to understand the strengths and weaknesses of tools uses to plan such critical projects.

Spreadsheet Models

The most common tool used for planning and managing Clinical Supply Chains are spreadsheet models. While this approach has some attractive qualities (simplicity, familiarity, and ease of sharing results) they suffer from several drawbacks.

For basic or static analysis, spreadsheets are often the right tool. However, supply chains are not static. They have parameters, resource constraints, queues, and demand curves that will change over time. This is where spreadsheet models show their limitations in capturing real-world situations. Although they will provide an answer, if you only use averages as your inputs, you will always get the average result, and not the range of real-world possibilities.

Simulation

Due to the drawbacks of spreadsheet models, approximately 10% of pharma companies have tried to solve these shortcomings by utilizing more sophisticated, dynamic tools like simulation. However, while simulation solves many of the shortcomings of spreadsheet models, they also introduce new problems; namely complexity and lack of transparency. Developing realistic simulations of supply chains is not an easy task because the software is often proprietary and the learning curve for programming them can be extremely high unless you are a data scientist or software developer.

Due to these barriers, the management of clinical trial supply chains and approaches to minimize costs has received little attention in formal research [Chen, Mockus, Orcun, & Reklaitis, 2012]. Much of the research that has been done does not consider the inherent randomness found in real-world clinical supply chain systems. This makes much of the research less applicable to pharma companies because uncertainty and variability is inherent to patient enrollment, shipment lead times, and process delays [Chen et al., 2012].

Alternatives

Given the challenges with both spreadsheet models and simulation, what are clinical trial supply chain decision makers to do? There are two possible solutions:

1) Develop highly intricate and complex simulation models using Discrete Event Simulation (DES) software like ExtendSim (https://goo.gl/VFSHak) or Python SimPy in hopes of capturing all the aspects of a complex supply chain; or

2) Simply eliminate the need and cost of the supply chain by providing subjects with a clinical study pharmacy card.

Some pharma companies take the first route and try to model complex clinical trial supply chains in hopes of maximizing efficiency and expediting clinical trials. Although not the easiest route, companies that wish to pursue this path would benefit from developing an understanding of dynamic programming and simulation optimization strategies. A good starting point would be a paper by Jung, Blau, Pekny, Reklaitis, and Eversdyk (2004), covering a simulation optimization approach to solve a generalized supply chain problem under demand uncertainty.

Using the RxStudyCard Instead of trying to build a large-scale simulation and then run hundreds of scenarios in hopes of identifying efficiencies, decision makers can simply eliminate much of it using a clinical study pharmacy card which leverages a network of over 60,000 retail pharmacies to deliver medicine and supplies to subjects participating in clinical studies. This type of program provides a safe and efficient method of dispensing unblinded medicines and supplies to study subjects that saves administrative effort, wasted supply overage, and time as well as reduces the amount of capital expense required by 30 to 60%, depending on the size of the study.

Chen, Ye, Linas Mockus, Seza Orcun, and Gintaras V. Reklaitis. “Simulation-Optimization Approach to Clinical Trial Supply Chain Management with Demand Scenario Forecast.” Computers & Chemical Engineering 40, no. Supplement C (May 11, 2012): 82–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compchemeng.2012.01.007.

Jung, June Young, Gary Blau, Joseph F. Pekny, Gintaras V. Reklaitis, and David Eversdyk. “A Simulation Based Optimization Approach to Supply Chain Management under Demand Uncertainty.” Computers & Chemical Engineering, Special Issue for Professor Arthur W. Westerberg, 28, no. 10 (September 15, 2004): 2087–2106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compchemeng.2004.06.006.

AlphaMD and MedSurgPI have entered into a partnership to provide comprehensive Product Development and Commercialization with Medical Affairs Services to clients worldwide. →

This service is a proprietary process to assist start-ups and established Life Science companies launch their drug, diagnostic and medical device products successfully from concept through launch and post-market surveillance. It encompasses proof-of-concept studies, clinical trial assistance, market research, product development, health economics and outcomes research services, a successful launch, data analytics and pharmacovigilance.

The Emergence of Population Health →

The Case for Vendor Oversight for Small Sponsors →

An Interview and Commentary by Kenya Oduor, PhD →

MD to Entrepreneur: From bedside to boardroom

Decreasing Pediatric Asthmatic Hospitalization & Emergency Visits By Improving Adherence

How Best to Leverage Medical Affairs Experts in Life Sciences Companies of Varying Size and Structure →

Shabnam Vaezzadeh, MD, MPA, Gerald L. Klein, MD, Peter C. Johnson, MD,

Valerie Riddle, MD, Robert L. Wolfert, PhD

Advantages of External Reviews and Audits in Biopharmaceutical Product Development →

Gerald L. Klein, MD (MedSurgPI), Celine Clive (Polaris Compliance Consultants),

Peter C. Johnson, MD (MedSurgPI), Laurie Meehan (Polaris Compliance Consultants),

Roger Morgan, MD (MedSurgPI) and Valerie Riddle, MD

Building Trust in Pharmaceutical Analytics →

David Lengacher (Rx Solutions), Gerald L. Klein, MD (MedSurgPI LLC), Peter C. Johnson, MD (MedSurgPI, LLC), Roger E. Morgan MD (MedSurgPI, LLC), Valerie Riddle MD and Brent Walter (Rx Solutions)

The Integrated Management Role of the Chief Executive Officer and the Commercial Chief Medical Officer →

Peter C. Johnson, MD*, June S. Almenoff, MD**, PhD and Gerald L. Klein, MD*

MedSurgPI, LLC*, Raleigh, NC and ** Independent Drug Development Consultant, Durham, NC*

Absorption and safety of serum-derived bovine immunoglobulin/protein isolate in healthy adults

Authors: Audrey L Shaw, PhD; David W Mathews, John E Hinkle, PhD; Bryon W Petschow, PhD; Eric M Weaver, PhD; Christopher J Detzel, PhD; Gerald L Klein, MD; Timothy P Bradshaw, PhD

Purpose: Previous studies have shown that oral administration of bovine immunoglobulin protein preparations is safe and provides nutritional and intestinal health benefits. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the plasma amino acid response following a single dose of serum-derived bovine immunoglobulin/protein isolate (SBI) and whether bovine immunoglobulin G (IgG) is present in stool or in blood following multiple doses of SBI in healthy volunteers. Methods: A total of 42 healthy adults were administered a single dose of placebo or SBI at one of three doses (5 g, 10 g, or 20 g) in blinded fashion and then continued on SBI (2.5 g, 5 g, or 10 g) twice daily (BID) for an additional 2 weeks. Serial blood samples were collected for amino acid analysis following a single dose of placebo or SBI. Stool and blood samples were collected to assess bovine IgG levels. Results: The area under the curve from time 0 minute to 180 minutes for essential and total amino acids as well as tryptophan increased following ingestion of 5 g, 10 g, or 20 g of SBI, with a significant difference between placebo and all doses of SBI (p<0.05) for essential amino acids and tryptophan but only the 10 g and 20 g doses for total amino acids. Bovine IgG was detected in the stool following multiple doses of SBI. No quantifiable levels of bovine IgG were determined in plasma samples 90 minutes following administration of a single dose or multiple doses of SBI. Conclusion: Oral administration of SBI leads to increases in plasma essential amino acids during transit through the gastrointestinal tract and is safe at levels as high as 20 g/day

The Experienced Medical Monitor: The Role of Virtual and Commercial Medical Monitor →

Facilitating the Biomedical Key Opinion Leader (KOL) Meeting with a Commercial Chief Medical Officer (CCMO) →

The Carmen Effect - And the Tyranny of Jargon →

The New C-Suite →

Peter C. Johnson, MD*, Matthew J. Pattison**, MSc, Jan Creidenberg***, Gerald L. Klein, MD*

* MedSurgPI, LLC, Raleigh, NC

** Anatomy HCD, Ltd, Brighton, UK

*** Strand Hill Resources, LLC, Kansas City, MO

DECREASING THE COSTS AND RISKS OF DRUG, DEVICE, AND DIAGNOSTIC DEVELOPMENT WITH A VIRTUAL MEDICAL OFFICER (VMO)

Medical Foods →

Gerald Klein, MD, Peter C. Johnson, MD and Renu Jain, PhD

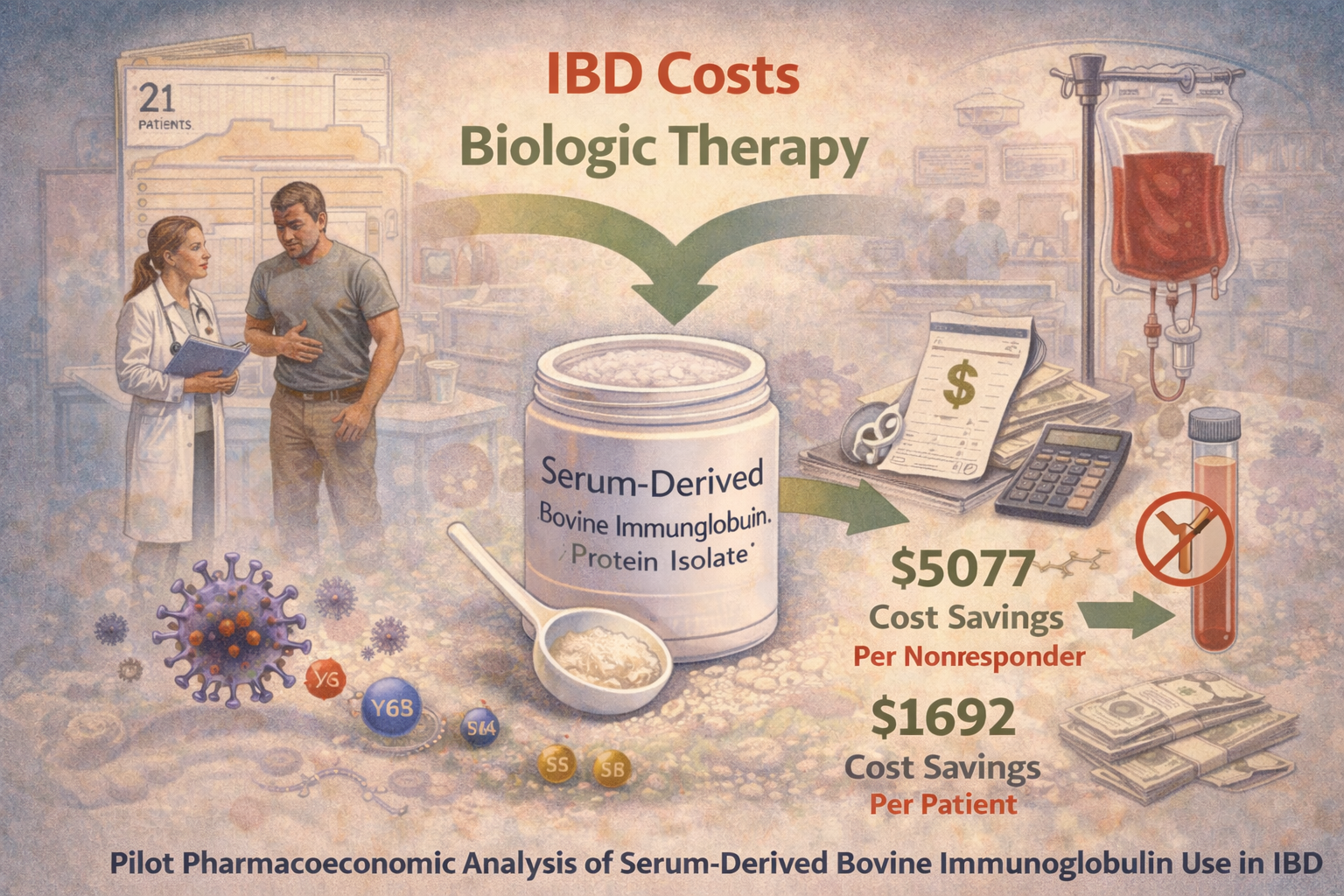

Pilot pharmacoeconomic analysis of serum-derived bovine immunoglobulin use in IBD

ABSTRACT

Objectives: Biologic therapy is commonly used to treat inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), but represents a significant cost in patient care. This pilot study analyzes the pharmacoeconomic benefit of utilizing a prescription oral medical food, serum-derived bovine immunoglobulin/protein isolate (SBI), for the management of IBD.

Study Design: Chart data from IBD patients who were administered SBI as part of an ongoing therapy (N = 21) were retrospectively collected from a gastrointestinal clinic.

Methods: Data regarding the management of IBD for the first 8 weeks in which patients used SBI were assessed and compared with the patients’ history of current and past use of biologics. Literature-reported prices for biologics and SBI were applied to these data, and the potential total costs savings per patient over the 8 weeks of analysis were calculated.

Results: Seven patients had a history of primary or secondary nonresponsiveness to biologics and inadequate management with current therapeutic regimens, suggesting that they would likely have to begin another biologic therapy due to disease severity. Incorporation of SBI at 5 g/day resulted in better overall management of their disease, alleviating the cost of impending biologic therapy. The difference between patients’ prior average 8-week biologic cost and the 8-week SBI cost equated to $5077 per nonresponder. This equated to $1692 per patient in the entire cohort.

Conclusions: Incorporation of SBI into the therapeutic regimen of this small cohort of IBD patients potentially correlates to a significant yearly savings, providing preliminary evidence for SBI as a cost-saving nutritive therapy to help manage IBD.